Postdoctoral Research

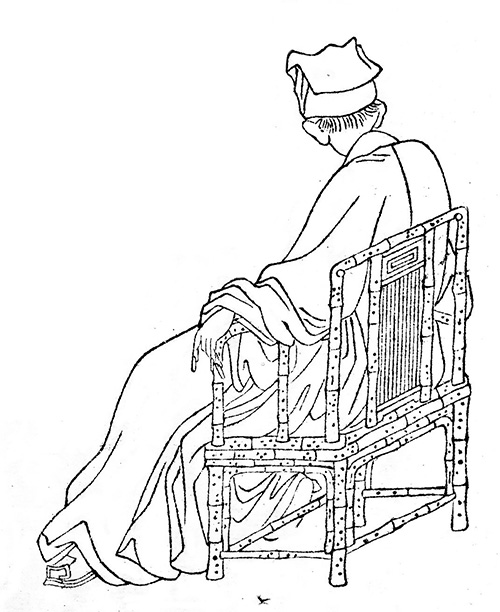

I am currectly engaged in a postdoctoral research entitled “Taming the Poisonous Dragon. Buddhist Metaphors, Allusions and Imagery in Wang Wei’s Poetry”. The main research question of the study is : how does the Tang dynasty poet Wang Wei 王維 (699–759) utilize Buddhist metaphors and other forms of figurative speech in his poetry? This question naturally divides into smaller sub-questions such as from which canonical sources Wang takes the tropes he uses, how does he make them an integral part of his artistic vision and what kind of philosophical and experimental landscapes do they seek to express?

Background of the study

According to the German historian Heinrich Dumoulin, the transplantation of Buddhism from its native soil in India to China from the latter half of the Han dynasty (202 BCE–220 AD) “may be counted among the most significant events in the history of religions.” A new high religion with a voluminous scriptural canon, sophisticated metaphysical doctrines and a system of moral guidelines arrived in China which already had its own long and complex intellectual history.

Apart from the realms of religion and philosophy, Buddhism also had a profound impact on Chinese literary culture in the centuries after the collapse of the Han. However, the new and somewhat alien religious paradigm posed intellectual challenges for the Chinese. For instance, the Chan school of Buddhism, which became eminent during the Tang dynasty (618–907), expressed deep scepticism towards language and verbal explanations. According to Christoph Anderl, the Chinese literati responded to these challenges by utilizing among other things “an extensive use of metaphorical, non-referential and poetic language.”

The Buddhism-inspired poetic language reached one of its apexes in the poetry of the Tang dynasty. Wang Wei, still widely know as shifo or the “Buddha of Poetry” in China, was one of the major Tang-era poets who repeatedly used Buddhist ideas, tenets, phrases and concepts in his writings. As I have argued elsewhere, Wang “was into just a conventional secular poet who injected Buddhist concepts and ideas superficially into his verses and only when they served his aesthetic purposes.” and that “Buddhism seems to have been for Wang a deep-rooted and lifelong conviction.”

Despite the fact that the influence of Buddhism in Wang Wei’s poetry is widely agreed upon, the mainstream of Wang scholarship has been limited by a superficial conception of Mahāyāna Buddhist philosophy and the lack of understanding of literary devices. Wang did not just mechanically copy Buddhist concepts from the scriptures to his writings but used them in creative and original ways and made them an integral part of his personal literary idiom. Analyzing his poetic strategies will enable us to understand better not only Wang’s poetry but also the wider literary world of Tang poetry.

Structure of the Study

Similes, metaphors, parables and symbols are elementary literary tropes in the rhetorical landscape of Mahāyāna Buddhist sutras and other doctrinal texts. Concepts such as nirvāṇa, emptiness and the Buddha nature cannot be directly described and hence the Buddhist tradition has created a rich treasury of indirect and allusive textual methods.

In this research, I analyse the ways Wang Wei utilizes this literal and intellectual reservoir in his poetry. He was undoubtedly extremely familiar with the Buddhist canon and it clearly serves as one of the spiritual sources from which he draws inspiration and textual material What I aspire to do with this study is to concentrate in a more detailed way on this poetic process and map out what texts and scripturesWang is actually using and, more importantly, how he is using them.

The research consists of three separate articles which, in the end, will be used as chapters of a monograph. The three articles are as follows:

1. Metaphors for the Mind

In the first chapter of the Platform Sutra, the most infuential Buddhist text written in China, a head monk named Shenxiu composes an (in)famous gāthā in which he likens the mind to a mirror that needs to be constantly dusted. Unsurprisingly, mirrors and other reflective surfaces are a common metaphor for the mind in Buddhist scriptures. So when Wang Wei in his poem “Facing the Snow on a Winter Evening and Thinking of the House of Layman Hu” 冬晚對雪憶胡居士家 talks about “cleaning the mirror to see one’s features in decline” 清鏡覽衰顏, the mirror, echoing Shenxiu’s verses, can be read as a metaphor for the mind and, in addition, appears to point at the importance of perceiving the human condition as realistically as possible.

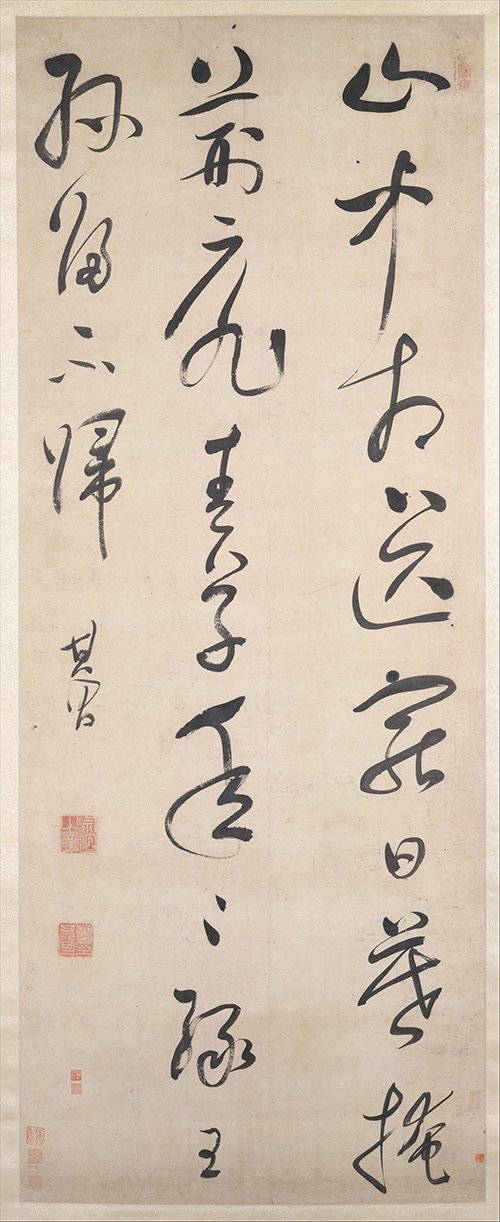

Wang utilizes similar metaphorical structures but in a more striking manner in the last couplet of his poem “Visiting Xiangji Temple” 過香積寺: “The curved pool is empty at dusk,/ the calm meditation tames the poisonous dragon” 薄暮空潭曲,安禪制毒龍. Here the empty pool symbolizes the surface of a tranquil mind under which an intense struggle of meditation practice is taking place. The metaphor of the “poisonous dragon” (dulong 毒龍) at the end of the poem is mentioned in several Buddhist texts, most notably in the 41st chapter of the Abhiniskramana Sutra 佛本行集經. Also, the Lotus Sutra, one of the main Mahāyāna scriptures, talks about suffering that appears in the form of “poisonous snakes” (dushe 毒蛇), which is clearly a variant of the poisonous dragon. So in Wang’s poem the calm pond (mind), the poisonous dragon (suffering) and the tranquil meditation form a conceptual triangle which illustrates, in a distinctly poetical way, the internal dynamics of spiritual cultivation.

In this article I will analyse metaphors conceptually connected to the mind and seek to elucidate the ways Wang uses them in his poetry.

2. Metapgors for Nirvāṇa

According to the sutras the Buddha refused to say anything about nirvāṇa, meaning the liberation from the cycle of rebirths and the ultimate bliss of salvation. For this reason, the Buddhist textual corpus has produced various indirect and figurative ways of talking about nirvāṇa. In his poem ”Suffering from the Heat” 苦熱 Wang Wei describes the physical torments caused by hot weather and on a symbolical level the situation refers to the sufferings of saṃsāra (the endless cycle of rebirths) . Solace arrives only when the speaker of the poem enters the “Sweet Dew Gate” 甘露門 which is a common metaphor for nirvāṇa in Buddhist scriptures. So on the metaphorical level the poems is speaking about spiritual conditions. However, seen from the point of view of the Mahāyāna notion of non-duality, the realms of saṃsāra and nirvāṇa are not separate, which means that the Sweet Dew Gate should not be understood as way escaping the heat but, on the contrary, as a way of accepting and embracing it.

Also, in his poem “Sitting Alone on an Autumn Night” 秋夜獨坐 Wang states that if one aspires to transcend sickness and old age, one needs to study the “un-born” 無生 which is a metaphor for the innate wisdom leading to nirvāṇa. In this kind of reading, nirvāṇa is less of an external condition and more of a metaphysical insight that rises from within.

In this article I will analyse these type of metaphors and tease out the ways they appear and function in Wang’s poetry.

3. Metaphors for Dreaming

Dreaming has been an important metaphorical concept in Chinese philosophy at least since the famous butterfly dream in Zhuangzi (3rd century BCE). The story features a philosopher dreaming of being a butterfly and after waking up, not being sure whether he is really a man or a butterfly. This means, essentially, that what is “real” and what is “dreamed” are mutually exclusive categories. However, in Buddhist texts their relationship is radically reinterpreted. For instance, the 32nd chapter of the Diamond Sutra instructs that one should perceive reality “as a dream, an illusion, a bubble, a shadow”. 如夢幻泡影”. Thereforse the sutra asserts, paradoxically, that one is able to see the true nature of reality only when one views it as a dream-like state. In other words, dream and dreaming do not refer to illusions and fantasies but serve as a metaphor for the true nature of reality.

Wang Wei was clearly familiar with the wording of the Diamond Sutra for in his poem “Sent to Layman Hu with Some Rice as He Lay Sick” 胡居士臥病遺米因贈he writes that “life and death are just illusions and dreams given to us” 生滅幻夢受. What the speaker is trying to tell his sick friend is that he should perceive his physical condition as a temporary state which has no real substance and thus transcend the illusory limitations of the human condition.

In this article I will analyse metaphors related to dreams and dreaming and seek to understand what kind of view of human life Wang Wei is trying to convey via these metaphors.

As can be observed, the themes of these three articles are closely linked with one another. On the level of literary analysis, I am especially interested in the ways metaphoric language guides and structures depictions of both external conditions and internal states in Wang’s poetry. These three articles will provide enough material for determining the rhetorical stances expressed in his verses. When these articles are transformed into a monograph at the completion of research, they will be preceded by a common introduction in which I will present the more general theoretical background of the articles.

The theoretical frame of reference of this study derives from two scholarly traditions. The research has, metaphorically speaking, one foot in classical sinology and the other in modern literary theory. The former refers to the numerous studies of Chinese Buddhism and classical Chinese poetry, the latter to modern theories on metaphors and the relationship between metaphoric language and thinking. In my study, these two intellectual traditions cross-pollinate one another and form a theoretical basis for my close readings of Wang’s poetry.

Significance of the Study

Wang Wei’s poetry is exceptionally fascinating because it is fed simultaneously from two separate cultural traditions: on the one hand from the rich array of Indo-Chinese Buddhist literary imagery and on the other from the long heritage of secular Chinese landscape poetry. Wang was arguably the most skilled poet of his age to combine these two elements in his verses and some scholars (e.g. Rafal Stepien and Jia Jinhua) have even suggested that his poetry exerted a notable influence on the later development of Chan Buddhism. For this reason, studying Wang’s poetry has a twofold benefit: it helps us better understand the religio-intellectual dynamics of classical Chinese poetry and at the same time elucidates the way poetry was able to take part in the development and enrichment of the textual corpus of Buddhism in Tang-era China. In this sense, the poisonous dragon is not merely an imposing image but it can also serve as a gateway to the metaphorical dimensions of Chinese Buddhist poetry.

About the Sources

As a primary sources of my research I will utilize The Collected Works of Wang Wei 《王維詩文集》edited by Chen Tiemin and The Collected Tang Poems 《全唐詩》edited by Peng Dingqiu et al.

There are several monographs on Wang Wei, both in English and Chinese, and they naturally form the basis of my research. The most notable of them are Pauline Yu’s The Poetry of Wang Wei, Yang Jingqing’s The Chan Interpretation of Wang Wei’s Poetry and Wu Qizhen’s (吳啟禎) 《王維詩的意象》. In addition, I will refer to several scholarly articles which include Nicholas Morrow Williaim’s “Quasi-Phantasmal Flowers: An Aspect of Wang Wei’s Mahāyāna Poetics”, Rafal Stepien’s “The Imagery of Emptiness in the Poetry of Wang Wei (王維699–761).” and Chen Yunji’s (陳允吉) “王維《鹿柴》詩 與大乘中道觀”.

Although all the studies mentioned above acknowledge the imprint of Buddhism in Wang’s writings, none of them addresses the topic from the point of view of metaphors. Since metaphoric language is essential to poetic writing, this presents a significant deficiency in the Wang scholarship.

The most important studies on the relationship between Chan Buddhism and Chinese poetry include Hsiao Li-hua’s (蕭麗華) 《唐代詩歌與禅學》, Sun Changwu’s (孫昌武) 《詩與禅》and Chen Yinchi’s (陳引馳) 《中古文學與佛教》and Xiao Chi’s (蕭馳.) 《佛法與詩境》. While Sun discusses the relationship between the Chan school and poetry on a rather general level, all the other books contain a whole chapter dedicated to Wang Wei and his relationship to Buddhism.

David L. McMahan’s Empty Vision: Metaphor and Visionary Imagery in Mahayana Buddhism is one of the few western studies on Buddhist metaphoric language. However, McMahan’s monograph focuses mainly on sutras and the instructional texts and leaves the Buddhist-inspired literature unexamined. In my research, I will seek to widen this horizon and bring poetry into the discussion.

In addition, an anthology Religion, Language and the Human Mind edited by Paul Chilton and Monika Kopytowska includes several articles which are useful to me when discussing the relationship between language and human cognition. For instance, Kurt Feyaerts’ and Lieven Boeve’s article “Religious Metaphors at the Crossroads between Apophatical Theology and Cognitive Linguistics” is a serious attempt to compare and make use of expertise from both theology and cognitive linguistics in analyzing religious discourse. The concept of “apophatic theology” resonates deeply with the linguistic scepticism of Chan Buddhism addressed in my research.

As for modern western literary theories, I will mostly lean on studies discussing the relationship between metaphors and thinking. George Lakoff‘s and Mark Johnson’s Metaphors We Live By is a landmark study of cognitive metaphor theory and serves as one of the groundlaying texts of my study. The ideas put forward by Lakoff and Johnson are further developed by Denis Donoghue in his book Metaphor . In addition, there are several articles in an anthology Metaphor and Thought edited by Andrew Ortony that are essential for my research. For instance, in his article “Language, Concepts and Worlds,” Samuel R. Levin attempts to develop accounts by which we could distinguish metaphors are they are used in everyday language and metaphors as they occur in in literature, particularly in poetry. These distictioms are also important in my discussion of poetic metaphors in Wang Wei’s writings.

LIST OF REFERENCES (A SELECTION)

Primary Sources

《王維詩文集 》(The CollectedWorks ofWangWei). Taipei: Sanmin shuju, 2009.

LIST OF REFERENCES (A SELECTION)

Primary Sources

《王維詩文集 》(The CollectedWorks ofWangWei). Taipei: Sanmin shuju, 2009.

《全唐詩》 (The Colledted Tang Poems) Ed. Peng Dingqiu et al. Beijing: Zhonghuo shuju, 2018.

《大正新脩大藏經》/The Taisho Canon) Edited by Takakusu Junjiro 高楠順次郎and Watanabe Kaigyoku 渡邊海旭. Tokyo: Taisho Issaikyo Kankokai, 1924–1935.

Secondary Sources

Adamek,Wendi L. The Mystique of Transmission: On an Early Chan History and Its Contexts. New York: Columbia University Press, 2007.

Broughton, Jeffrey Lyle. Zongmi on Chan. New York: Columbia University Press, 2009.

Chen Yinchi 陳引馳. Sui Tang foxue yu zhongguo wenxue. 隋唐佛學與中國文學(Sui and Tang Buddhist Studies and Chinese Literature). Nanchang: Baihua zhou wenyi chubanshe, 2010.

———. Zhong gu wenxue yu fojiao 中古文學與佛教 (Chinese Literature and Buddhism in the Middle Ages). Beijing: Commercial Press, 2017.

Chen Yinchi and Jing Chen. “Poetry and Buddhist Enlightenment:WangWei and Han Shan.” In How to Read Chinese Poetry in Context: Poetic Culture from Antiquity through the Tang, edited by Zong-qi Cai, 205–22. New York: Columbia University Press, 2018.

ChenYunji 陳允吉. Tangyin fojiao biansi lu 唐音佛教辨思録( The Record of Analysis of Tang-Style Buddhism). Shanghai: Shanghai guji chubanshe, 1988.

———. “Wang Wei ‘Lucha’ shi yu dasheng zhongdao guan” 王維《鹿柴》詩與大乘中道觀(WangWei’s Poem “Deer Park” and the Mahayana View of the MiddleWay). In WangWei yanjiu (di si ji) 王維研究(第四輯) (WangWei Studies,Vol. 4), 56–64. Liaoning: Liaohai chubanshe, 2011.

Chou, Shan. “Beginning with Images in the Nature Poetry of Wang Wei.” Harvard Journal of Asiatic Studies 42, no. 1 (1982): 117–37.

Chilton , Paul and Monika Kopytowska (eds.). Religion, Language, and the Human Mind. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2018.

Cole, Alan. Patriarchs on Paper: A Critical History of Medieval Chan Literature. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2016.

Donoghue, Denis. Metaphor. Cambridge, MA Harvard University Press, 2014.

Dumoulin, Heinrich. India and China. Vol. 1 of Zen Buddhism: A History . Translated by James W. Heisig and Paul Knitter. Bloomington, IN: World Wisdom, 2005.

Eifring, Halvor. “Beyond Perfection: The Rhetoric of Chán Poetry in Wáng Wéi’sWang Stream Collection.” In Zen Buddhist Rhetoric in China, Korea, and Japan, edited by Christoph Anderl, 237–64. Leiden: Brill, 2012.

Faure, Bernard. Chan Insights and Oversights: An Epistemological Critique of the ChanTradition. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1993.

Greene, Erik M. Chan before Chan: Meditation, Repentance, and Visionary Experience in Chinese Buddhism. Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press, 2021.

Hsiao Li-hua 蕭麗華. Tangdai shige yu chanxue 唐代詩歌與禅學 (Tang Dynasty Poetry and Chan Studies). Taipei: Dongda tushu gufen youxian gongsi, 1997.

Lakoff, George and Mark Johnson. Metaphors We Live By. Chigaco: University of Chicago Press, 2008.

Owen, Stephen. The Great Age of Chinese Poetry: The High Tang. Rev. ed. Melbourne: Quirin, 2013.

———. “How Did Buddhism Matter inTang Poetry?” T’oung Pao 103, fasc. 4–5 (2017): 388–406.

Sharf, Robert H. “Mindfulness and Mindlessness in Early Chán.” In Meditation and Culture: The Interplay of Practice and Context, edited by Halvor Eifring, 55–75. London: Bloomsbury, 2017.

Ortony, Anderw (ed.). Metaphor and Thought. 2Nd edition. Cambridge: Cambridge Unuversity Press, 1993.

Stepien, Rafal. “The Imagery of Emptiness in the Poetry of Wang Wei (王維699–761).” Interdisciplinary Literary Studies 16, no. 2 (2014): 207–38.

Sun Changwu’ 孫昌武. Shi yu chan 詩與禅 (Poetry and chan). Taipei: Sanming shuju, 11994.

Wagner, Marsha L. “The Art ofWangWei’s Poetry.” PhD diss., University of California, Berkeley, 1975.

Walser, Joseph. Genealogies of Mahāyāna Buddhism: Emptiness, Power, and the Question of Origin. London: Routledge, 2018.

Wawrytko, Sandra A. “The Sinification of Buddhist Philosophy: The Cases of Zhi Dun and The Awakening of Faith in the Mahāyāna (Dasheng Qixin Lun).” In Dao Companion to Chinese Buddhist Philosophy, edited by YouruWang and Sandra A.Wawrytko, 29–44. Dordrecht: Springer, 2018.

Weinstein, Stanley. Buddhism under the T’ang. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1987.

Welter, Albert. Monks, Rulers, and Literati: The Political Ascendancy of Chan Buddhism. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2006.

Williams, Nicholas Morrow. “Quasi-Phantasmal Flowers: An Aspect of Wang Wei’s Mahayana Poetics.” Chinese Literature: Essays, Articles, Reviews 39 (2017): 27–53.

Williams, Paul. Mahāyāna Buddhism: The Doctrinal Foundations. 2nd ed. London: Routledge, 2009.

Wu Qizhen 吳啟禎. Wang Wei shi de yixiang 王維詩的意象 (The imagery of Wang Wei’s poetry). Taipei: National Library Press, 2008.

Xiao Chi 蕭馳. Fofa yu shijing 佛法與詩境 (B uddhadharma and the Realm of Poetry). Taipei: Linking Books, 2012.

Yang, Jingqing. The Chan Interpretation of Wang Wei’s Poetry: A Critical Review. Hong Kong: Chinese University Press, 2007.

Yü, Chün-fang. Chinese Buddhism: A Thematic History. Honolulu: University of Hawai‘i Press, 2020.

Yu, Pauline. The Poetry ofWangWei: New Translations and Commentary. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1980.

Zhao Changping 趙昌平. “WangWei yu shanshuishi xuanqu xiangzhong chanqu de zhuaihua” 王維與山水詩玄趣向重禪趣的轉化(Wang Wei and Landscape Poetry’s Transfer from Xuan-Significance to Chan-Significance). In Huixiang ziran de shixue 迴向自然的詩學 (Studies of Nature-Oriented Poetry), edited by Tsai Yu 蔡瑜, 229–58. Taipei: National Taiwan University Press, 2012.

Zürcher, Erik. The Buddhist Conquest of China: The Spread and Adaptation of Buddhism in Early Medieval China. Leiden: Brill, 2007.